Bonobos Capture Baby Monkeys and Use Them as Doll

Abstract

Chimpanzees and bonobos are highly capable of tracking other's mental states. It has been proposed, however, that in contrast to humans, chimpanzees are just able to exercise this in competitive interactions simply this has rarely been directly tested. Here, pairs of chimpanzees or bonobos (Study ane) and 4-year-old children (Written report 2) were presented with two almost identical tasks differing only regarding the social context. In the cooperation status, players' interests were matched: they had to make corresponding choices to be mutually rewarded. To facilitate coordination, subjects should thus make their actions visible to their partner whose view was partially occluded. In the competition condition, players' interests were directly opposed: the partner tried to match the subject field's choice but subjects were only rewarded if they chose differently, and then that they benefited from hiding their actions. The apes successfully adjusted their decisions to the social context and their functioning was markedly better in the cooperation condition. Children as well distinguished betwixt the two contexts, merely somewhat surprisingly, performed amend in the competitive condition. These findings demonstrate experimentally that chimpanzees and bonobos can accept into business relationship what others tin can run into in cooperative interactions. Their social-cognitive skills are thus more flexible than previously assumed.

Introduction

Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) are able rail what others perceive, know, and intend, and they readily exercise so to predict other's actions1,2,3,iv,v,6,7. Although less studied, bonobos (Pan paniscus), who shared a common ancestor with chimpanzees near ii two million years agone, appear to have comparable social-cognitive abilitieseight,9,10,11,12. These abilities, which are central for human forms of cooperation, communication, and culture13, 14, thus have deep phylogenetic roots.

However, a hit characteristic of these studies is that they have mostly used competitive settings: the apes had to use their mental state understanding to gain an reward over a man or conspecific partner in a contest over food. By comparison, experiments investigating chimpanzee social-cognitive skills in cooperative scenarios have yielded largely negative resultsfifteen,16,17,18. This has led to the proposal that due to the competitive nature of their social lives, chimpanzees generally display greater social-cognitive skill in competitive than in cooperative contexts (sometimes chosen the competitive cognition hypothesis19,twenty,21). This is in stark contrast to human being children who reliably display these abilities in cooperative contexts from early in evolution22,23,24.

A pregnant drawback of the competitive knowledge account, notwithstanding, is that chimpanzees have rarely been tested in paradigms that differed only in terms of social context (i.e., cooperation versus competition) but were identical in virtually other respects25. In i of the few exceptions, chimpanzees were presented with an object selection task in which food was subconscious underneath one of 2 cups. In 1 condition, a cooperative experimenter pointed to the cup containing the nutrient in an effort to inform subjects of its location whereas in another condition, a competitive experimenter reached for the baited cup and attempted (but failed) to access the nutrient herself. The consistent finding was that chimpanzees only successfully inferred the location of the food in the competitive status, thus lending some back up to the competitive cognition hypothesisxx (come across also ref. 26).

Understanding this kind of cooperative communicative intention plays a key role in human being everyday interaction and comes naturally to human infants27,28,29. However, this is only one specific type of cooperative interaction and the failure of chimpanzees to comprehend altruistically motivated chatty acts, especially when provided by a human partner, may not be indicative of their skills in cooperative contexts beyond the board (this is peculiarly and then considering chimpanzees are non known to naturally produce such cooperative chatty acts for one another).

A unlike example of cooperative interaction in humans is i in which multiple individuals piece of work together collaboratively and mutualistically, equally when collectively foraging or building things togetherthirteen, 30, 31. Chimpanzees and bonobos besides appoint in mutually beneficial collaborative activities in their natural habitat every bit, for example, when hunting for monkeys or teaming upwardly with partners during conflicts32,33,34,35,36 and this has been demonstrated in experimental contexts as well37,38,39. An important divergence is that these interactions do non necessarily crave individuals to ascribe benevolent intentions to others. Instead, and similarly to competitive scenarios, it is sufficient to assume cocky-serving intentions or to simply projection ane's own preferences onto others (east.thou., but like myself, my partner wants to catch the monkey). Taking into business relationship other's mental states seems especially relevant to making expert decisions in mutualistic contexts (e.g., Does my partner know where the monkey is? Which monkey can my partner see?), so that, perhaps, apes are more likely to display social-cognitive abilities in this kind of interaction. Whether chimpanzees and bonobos are able to do this or if these skills are indeed restricted to competitive settings is shortly unresolved.

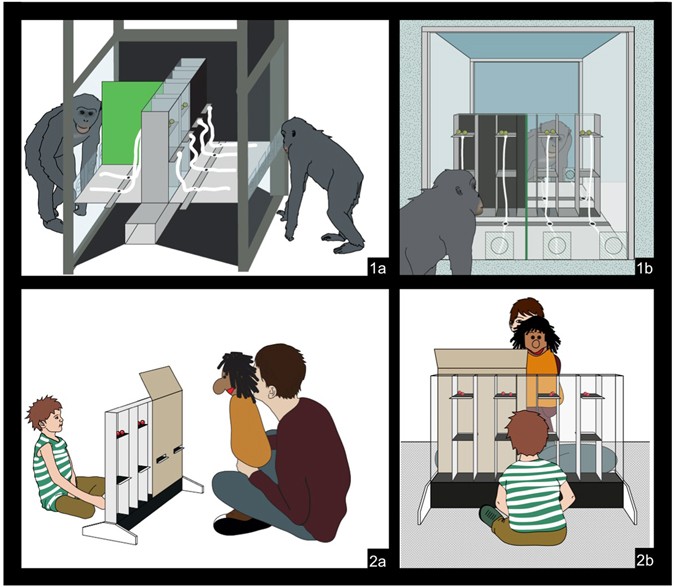

The current study attempted to make full this gap. In an experimental setting, pairs of apes (and, in a 2nd study, human children) were presented with an apparatus in which they could either hide or display their actions to their partner whose visual access to the apparatus was partially blocked past a barrier (Fig. 1). In the cooperation status, both players had identical interests: past choosing to act on the aforementioned part of the apparatus they received one advantage each. To facilitate coordination, subjects should therefore choose a part of the apparatus visible to their partner. In the competition condition, in contrast, players' interests were directly opposed: the partner still tried to match the subject'due south option, but the subject only received a reward past choosing a different part of the apparatus from their partner. They should therefore cull a role of the appliance not visible to their partner. In both conditions, therefore, subjects could benefit from taking into account what their partner could come across, the divergence beingness that in one condition they cooperated mutualistically while in the other condition they competed.

Experimental setup. 1a) Setup of Study 1 – the subject (left) chooses starting time, the stooge partner (right) chooses 2d; 1b) Apparatus from the subject field's perspective – subjects can run into the whole apparatus, the partner's view is partially blocked by a barrier; 2a) Setup of Study 2 – children cull first, the partner (a puppet played by E2) chooses second; 2b) Apparatus from the kid's perspective, the puppet'southward view is partially blocked by a barrier. (copyright holder: Max Planck Society).

To increase the external validity of the study, subjects interacted with conspecific partners rather than human experimenters. If apes are indeed better at applying their social-cognitive skills in competitive settings, they should perform better in the competitive than in the cooperative condition. By contrast, if they can apply their skills in both contexts equally, and failure in previous experiments was due to the specific kind of cooperative activity, subjects should succeed in both tasks. For comparing, we also tested preschool children in a second study using coordinating tasks (Study 2). Since preschoolers have previously been shown to understand what others can see we predicted children to successfully adapt their decisions to the social context and to perform well in both tasks.

Results

Study 1a (between-subjects)

A Generalized Linear Mixed Model (GLMM) revealed that the apes chose the visible option significantly more often in the cooperation condition than in the competition condition (χ2 = four.44, df = 1, p = 0.035) providing a offset indicator that they adjusted the visibility of their choices depending on the social context in the direction predicted. The model controlled for species (chimpanzee vs. bonobo), barrier position, session and trial number, the random effects of subject ID and the social group, and the random slopes of barrier position, session, and trial number nested within subject ID (run into Method section and Supplementary Information for details on these predictors and Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 for detailed model descriptions and outputs).

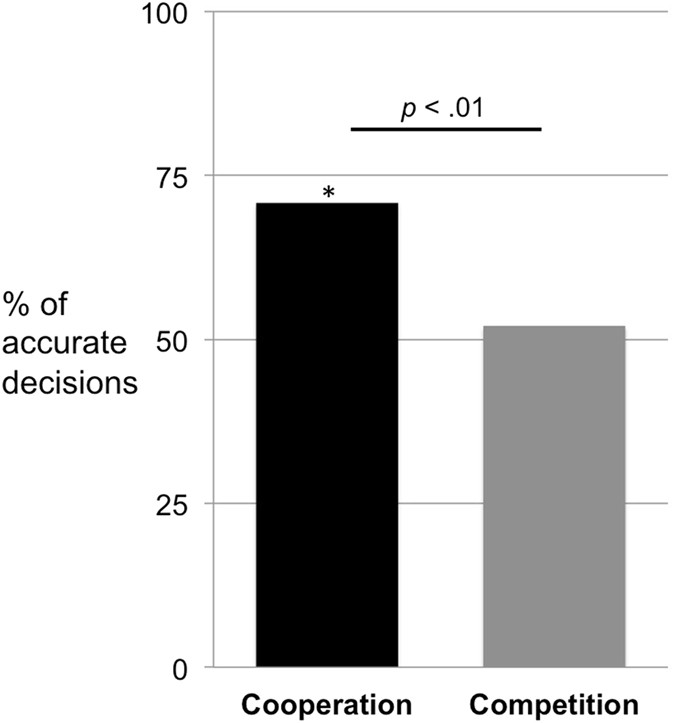

A second GLMM examined subject's tendency to brand accurate decisions (i.e. visible choices in the cooperation condition and hidden choices in the competition status). Subjects in the cooperation condition fabricated significantly more accurate decisions than subjects in the competition condition (χ2 = vii.14, df = 1, p = 0.008; Fig. 2) and chimpanzees made more accurate decisions than bonobos (χtwo = 4.21, df = 1, p = 0.040). The model included the same predictors, random effects, and random slopes every bit the first GLMM, with the simply difference that species was treated as a test predictor to investigate potential species differences in task performance.

Report 1a – % of accurate decisions – i.e. visible decisions in the cooperation condition and hidden decisions in the competition condition – by chimpanzees and bonobos (out of 24 trials). *In a higher place chance (p < 0.05).

Further analyses revealed that subjects chose the right option significantly in a higher place chance (i.e., 50%) in the cooperation condition (mean = 17 (seventy.8%), SD = 3.35, t(five) = three.66, p = 0.015) just not in competition condition (hateful = 12.5 (52.i%), SD = 3.78, t(5) = 0.32, p = 0.759). Session or trial number did not take a significant effect in any of the models.

Written report 1b (within-subjects)

Report 1a provided start strong experimental evidence that chimpanzees and, to a bottom caste, bonobos are able to have into account what others can encounter in cooperative interactions. These skills thus do not appear to be restricted to competitive contexts per se. A surprising finding, however, was that subjects actually performed meliorate in the cooperative than in the competitive status. To further examine the flexibility of the apes' abilities and to reduce the likelihood that these results were influenced by random assignment we presented subjects with the identical experiment over again, except that individuals who had previously taken part in the cooperation status now participated in the contest condition (and vice versa).

To analyze the complete dataset, we ran the same two GLMMs as in Written report 1a except that we included the experimental phase and the interaction betwixt condition and stage as additional test predictors to notice potential order effects. The interaction between condition and phase did not significantly touch subjects' tendency to brand their choices visible (χ2 = 0.02, df = 1, p = 0.885) and was therefore dropped from the model. The main effect of phase was besides not pregnant (χii = 1.31, df = 1, p = 0.252). Even so, and confirming the results of Report 1a, apes chose the visible pick significantly more often in the cooperation condition than in the contest condition (χ2 = 9.11, df = 1, p = 0.003).

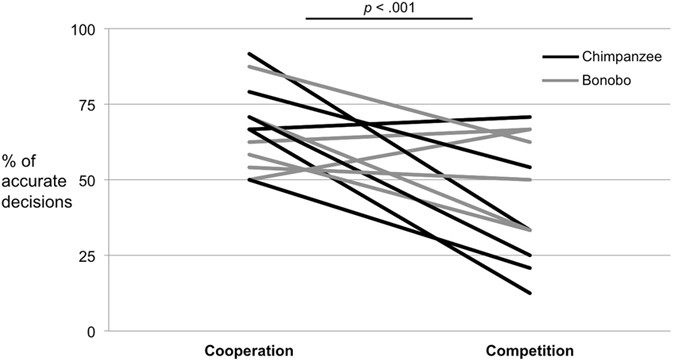

In the GLMM analyzing decision accuracy the interaction between phase and status was also not significantly (χ2 = 1.59, df = ane, p = 0.207) and was thus dropped from the model. Nonetheless, subjects made significantly more than accurate decisions in the cooperation than in the competition condition (χtwo = 37.40, df = 1, p < 0.001), thus confirming the upshot of Study 1a (Fig. 3). The species difference constitute in Study 1a was not confirmed (χ2 = 0.21, df = one, p = 0.645). Moreover, subjects made significantly more accurate decisions in phase ane than in phase 2 of the experiment (χ2 = 8.47, df = 1, p = 0.004).

Study 1b – % of accurate decisions – i.east. visible decisions in the cooperation status and hidden decisions in the competition status – by individual chimpanzees and bonobos (out of 24 trials per status).

Further analyses revealed that, overall, subjects chose the right option significantly in a higher place chance in the cooperation condition (hateful = xvi.25 (67.7%), SD = three.25, t(11) = 4.53, p = 0.001) merely not in competition status (mean = 10.58 (44.one%), SD = 4.83, t(eleven) = −1.02, p = 0.332). Again, session or trial number did not have a pregnant effect in whatsoever of the models.

Follow-upward preference test

To further investigate the issue that subjects fabricated more correct choices in the cooperation condition than in the competition condition we ran an additional preference test to assess whether the apes might have a baseline preference for making visible or subconscious choices in the presence of a partner in a neutral context. Subjects (including individuals who had non participated in the chief experiment) could choose 1 of four baited trays, two of which were occluded by a bulwark from a partner's view (equally in the main experiment). The partner remained passive and could not access any food.

Subjects did not show a preference for visible trays: choices were not different from chance (mean = 12.45 (51.nine%), SD = 2.58, t(nineteen) = 0.81, p = 0.427) suggesting that the difference in performance in the main weather is unlikely to be due to a baseline preference for the visible options (there was no significant deviation between subjects who had taken part in the main experiment and those who had non, t(18) = 0, p = 1).

Report ii

For comparison, we ran an coordinating written report with four-year-old children. This age group was chosen since previous research has demonstrated first competencies at this age in other cooperative coordination problems40, 41. While previous studies have shown that visual perspective taking skills are present by four years of age42, 43 it has rarely been examined in how far children can apply these skills in strategic interactions. Moreover, and similar to research with apes, this has not been studied in tasks comparable in their overall structure but varying in terms of the social context. Children were thus presented with about identical tasks as the apes (with but pocket-size adjustments, see Method department) in a between-subjects blueprint.

Choices

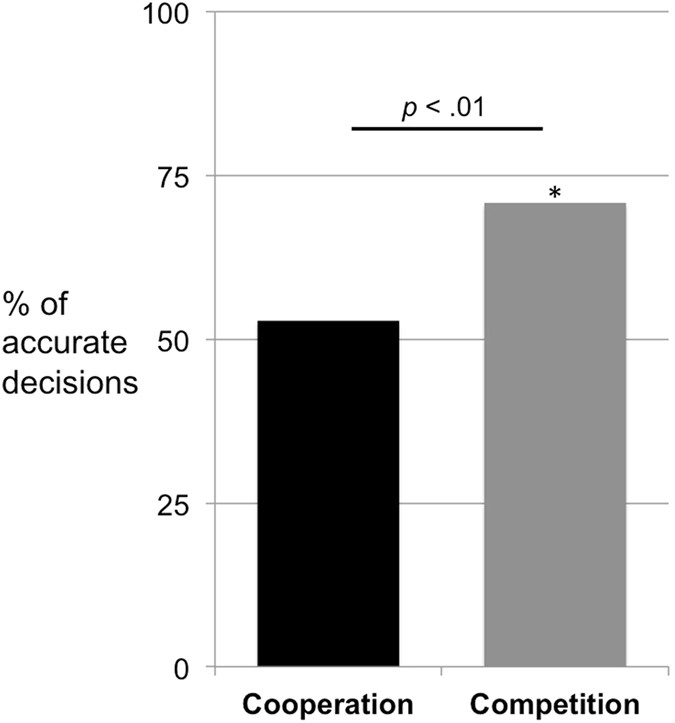

To clarify children's choices nosotros ran a GLMM with condition equally the merely test predictor while controlling for trial number, identity of the second experimenter, barrier position, the random effect of subject ID, and the random slopes of trial number and bulwark position nested within subject ID (come across Method department and Supplementary Data for details on the predictors and Supplementary Tables S3 and S4 for detailed model descriptions and outputs). In line with our predictions, children chose the visible option significantly more often in the cooperation status than in the competition status (χ2 = 9.37, df = ane, p = 0.002; Fig. iv). A second GLMM (using the same test and control predictors) indicated that children made fewer right choices in the cooperation than in the competition condition (χtwo = nine.61, df = 1, p = 0.002). Further analyses showed that children chose the correct option in a higher place adventure in the competition condition (mean = 4.25 (lxx.8%), SD = one.seventy, t(23) = 3.44, p = 0.002) merely not in cooperation condition (mean = iii.17 (52.eight%), SD = 1.66, t(23) = 0.492, p = 0.627).

Report 2 – % of accurate decisions – i.e. visible decisions in the cooperation status and subconscious decisions in the contest condition – past children (out of 6 trials). *To a higher place take a chance (p < 0.01).

Postal service-test questions

As an additional measure of children's understanding of the task they were asked after the test: "When was it easier for you to win the marbles – when you pulled backside the barrier or when you pulled where there was no barrier?" Children in the cooperation status were more probable to bespeak the visible options than children in the competition condition (Fisher's Exact Test, p = 0.005). The number of accurate decisions children made at test was positively related to the accuracy of children'due south responses (i.e. to refer to the visible options in the cooperation condition and to the hidden options in the competition condition; GLM (Generalized Linear Model): χ two = iv.71, df = i, p = 0.030). Moreover, children in the cooperation condition provided more accurate answers than children in the competition condition (χ2 = 5.86, df = 1, p = 0.015), which contrasts with their decisions at examination where they were more accurate in the competition condition.

Children were and then asked: "Why was it was easier to win marbles there?" A GLM indicated that the number of accurate decisions at test was positively related to children'south trend to refer to their partner's perceptual or noesis state (e.g. "because she could encounter the marbles there" subsequently indicating the visible options in the cooperation condition, or "considering she didn't know which tower I chose" after indicating the hidden options in the competition condition; χii = 12.77, df = 1, p < 0.001). The experimental condition did not significantly affect the accuracy of children's responses (χ2 = 0.29, df = 1, p = 0.590).

Follow-upward preference exam

A like preference test as with the apes was run with a new sample of children. The appliance was rigged so that children were able to retrieve rewards individually while the partner remained passive. The training and test mimicked the main experiment equally closely as possible. Children's choices in the preference examination were not different from chance (mean = iii.13 (52.ii%), SD = 1.36, t(23) = 0.45, p = 0.657) suggesting that children'southward choices in the test conditions were not influenced by a baseline preference for hidden or visible options.

Word

Our findings indicate that the ability of chimpanzees and bonobos to recruit their social-cognitive skills is not restricted to competitive interactions: apes in the current study successfully adjusted the visibility of their decisions depending on whether they cooperated or competed with a partner, and strikingly, they performed particularly well in the cooperative chore.

This is in stark dissimilarity to previous studies investigating chimpanzee social-cerebral skills in cooperative interactionsfifteen,16,17,xviii. Dissimilar the current study, even so, past research largely investigated apes' abilities in the context of donating communication. For instance, chimpanzees have been shown to fail to reliably call back food subconscious underneath 1 of 2 cups fifty-fifty though an experimenter had previously pointed to the baited loving cup20. Crucially, subjects in this task were not only required to cover that the experimenter knew about the location of the food simply also that she had the benevolent intention to inform subjects of its whereabouts – something that does non appear to occur naturally amongst chimpanzees.

By contrast, the mutualistic context of the current study meant that subjects did non take to ascribe intentions to their partner that differed from their own. Instead, and merely equally in the competitive condition (also every bit in competitive tasks used by Hare and colleagues1), they simply had to presume that, like themselves, their partner intended to access the food. This may accept enabled them to treat their partner every bit a 'social tool' that they could use to reach an individualistic goal44. Moreover, chimpanzees and bonobos accept been shown to cooperate mutualistically in the wild and in laboratory settings so that this may be a context in which they are naturally capable of displaying their social-cognitive abilities. An additional advantage of the current study was that subjects interacted with conspecific partners rather than homo experimenters which added to the external validity. The absence of an event of session or trial number and the observation that performance did not drop when the bulwark position inverse further suggests that the electric current findings cannot be explained by learning during the exam sessions.

Unexpectedly, however, subjects' performance was amend in the cooperative than in the competitive condition which conflicts with previous studies using competitive scenarios1,two,3,iv,v,six,7. Why the apes failed to adapt the visibility of their choices in the competitive chore of the current report is not entirely clear. One possibility, that the apes have a baseline preference for the visible options, was refuted by the absence of such a preference in the mail service-examination preference exam. An alternative is that even though the apes received extensive experience with the competitive context at training and successfully completed all benchmark tests subjects may have understood the setup of cooperative chore ameliorate than the setup of the competitive job. The possibility that the observed difference between atmospheric condition was due to differences in task understanding thus cannot be fully excluded.

It is of import to notation, still, that some previous studies examining chimpanzees' social-cognitive skills in competitive contexts accept besides yielded negative results. For instance, in a contempo study by Karg and colleagues chimpanzees successfully revealed food to a helpful experimenter who gave them any visible food (although they did so rarely before the experimenter approached in apprehension of her deportment) but failed to manipulate the same apparatus such that food was concealed from a competitor's view45. A parallel betwixt this study and the current ane is that in dissimilarity to previous studies1,ii,3 subjects were not required to hide themselves or to consider whether or not another individual had seen some food being subconscious just to direct dispense the rewards while anticipating what their partner would encounter when information technology was their turn to cull. This may accept added complexity in both this and the current tasks. Given the wealth of evidence showing chimpanzees' abilities to use their social-cognitive skills in competitive interactions the findings of the current studies should not exist interpreted as suggesting that chimpanzees are better at using these skills in cooperative than in competitive interactions. They do suggest, notwithstanding, that their abilities to use these skills may be influenced by contextual factors that are not withal fully understood and crave further investigation.

Importantly, the current findings provide some first strong experimental show that chimpanzees and bonobos are able to use their social-cerebral abilities in order to successfully coordinate decisions with conspecifics in a cooperative context. Reverse to previous suggestions19,xx,21, these abilities may thus not be restricted to competitive interactions. This corresponds to the contempo finding that wild chimpanzees selectively inform ignorant group members of danger46 which likewise points to the determination that chimpanzees can recruit their agreement of other's mental states more flexibly and across social contexts.

In the second study, iv-twelvemonth-old children also successfully adapted their decisions to the social context and chose the visible choice significantly more often in the cooperation condition than in the competition condition. The significant relation betwixt children's performance at test and their ability to correctly answer to the post-test questions (i.e., their verbal task understanding and the tendency to explicitly refer to their partner's perception or cognition) further underlines that children did indeed solve the task by taking into account their partner'south mental states.

Somewhat surprisingly, however, children performed ameliorate in the competition status than in the cooperation status and, as with the apes, this finding is unlikely to exist accounted for by a baseline preference for hidden or visible options as indicated by the follow-up preference test. In contrast, previous enquiry has shown that children at this age tin can take into account what others can see and how this differs from their own perspective42, 43, 47 and besides readily recruit communication and complex theory of mind skills for cooperative purposesforty, 41, 48.

While unexpected, several reasons may account for this finding. First, many games that children meet in their daily lives involve some form of contest49 then that children may find it more intuitive to compete with others in social game contexts. Relatedly, the partner'due south motive to steal marbles may have been particularly salient, leading children to exist more attuned to the test situation in the competitive condition.

On the other mitt, children in the cooperation condition were very capable of accurately answering the post-test questions suggesting that the discrepancy in performance betwixt conditions may take been due to differences in motivation rather than comprehension. Thus, some other possibility is that children did empathise that choosing the visible options e'er resulted in a certain outcome (i.due east., always winning in the cooperation condition and e'er losing in the competition condition) and that hiding their conclusion made the game more than exciting, despite the fact that this resulted in lower rates of overall success in the cooperation condition. The introduction of new rewards at test (gold marbles, see method section) was an attempt to prevent such alternative motives simply the possibility that choosing backside the barrier in the cooperation condition may simply have been more fun cannot be fully excluded.

Finally, previous research has shown that social engagement can sometimes pb children to overestimate other's knowledge50. In this written report, 2-yr-olds played with an object an adult could non come across. When the developed remained co-nowadays – simply not when she disengaged from the interaction – children often erroneously assumed the developed to exist acquainted with the object. Something similar may potentially accept been at play in the current experiment although it is unclear why this should have exclusively afflicted the cooperation condition. What speaks in favor of this explanation, however, is that, on a few occasions, children in the cooperation condition chose an option behind the barrier so – invisible to the partner – pointed to that pick as if attempting to inform the partner which tower to choose. Hence, given that children could e'er brand common middle contact and communicate with their partner some participants may have assumed their own decisions to be mutually known, a possibility worth investigating farther in futurity experiments.

In conclusion, the current study demonstrates that chimpanzees and bonobos are able to recruit their agreement of other's minds more flexibly than ordinarily thought. Whereas these abilities have been suggested to be largely restricted to competitive settings the current investigation shows experimentally that chimpanzees and bonobos are also able to have into business relationship what others can see in guild to cooperate with conspecifics for mutual benefit. This attests to chimpanzees' and bonobos' cooperative abilities in mutualistic contexts. The written report further highlights the importance of investigating the influence of the social context on the use of social-cognitive skills in humans and other apes past using comparable experimental paradigms.

Method

Study 1a

Subjects

Eight chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes, 3 females, M age = 14 years) from two unlike social groups and 4 bonobos (Pan paniscus, 3 females, Grand age = xvi years) were included in the final sample (for a total subject area list see Supplementary Tabular array S5). Five additional chimpanzees and iii bonobos did not complete the training and were not included in the test. Two further chimpanzees and i bonobo acted as stooge partners. All were housed in social groups in at the Wolfgang Köhler Primate Research Center. Subjects were randomly allocated to the cooperation or the contest condition (betwixt-subjects blueprint) with the constraint that per status there was an equal number from each species.

The study complied with the European and Globe Associations of Zoos and Aquariums (EAZA and WAZA) Upstanding Guidelines and was approved by the joint Ethics Committee of Leipzig Zoo and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Subjects were never food-deprived and water was available throughout testing. Participation was voluntary and could be refused at any time.

Apparatus and design

The test apparatus was a transparent plexi-glass box including 4 side by side towers (45 cm high, 6 cm wide, with 8 cm space between them). Each tower independent two platforms – an upper and a lower one – and ropes were attached to the platforms. The "proposer" could access the ropes fastened to the upper platforms and the "responder" the ones fastened to the lower platforms (proposer and responder were in adjacent rooms). Two rewards were placed on each upper platform. To admission a rope subjects had to lift a decision door in front of that rope. This ensured that they could not pull more than one rope simultaneously. Once subjects had made a choice (i.eastward. pulled ane rope) the experimenter moved the other ropes out of attain.

In each trial, the proposer started by pulling a rope, causing the corresponding platform to collapse and the rewards to autumn downwards onto the lower platform. The responder then collapsed a lower platform. Advantage dispersal was controlled via a series of plastic ramps invisible to the apes and worked differently depending on the status. In the cooperation condition, rewards ending up at the bottom of the towers were divided every bit between proposer and responder. Hence, if both collapsed platforms of the same belfry they each received 1 reward. If they chose unlike towers no histrion could admission the rewards.

In the competition condition, the responder had exclusive access to all rewards at the bottom of the towers so that by choosing the same belfry as the proposer the responder could steal all rewards. The proposer received all rewards remaining on the lower platforms. That is, if the responder chose a different tower than the proposer the experimenter waited a few seconds, switched the position of the ramps, and collapsed the lower platforms so that all rewards of the belfry the bailiwick had chosen rolled to the subject's side while the partner received nothing. Hence, in the cooperation condition players were incentivized to coordinate on the same tower. In the competition condition, the responder's goal was to collapse the platform of the aforementioned tower every bit the proposer but the proposer's goal was for both to choose different towers.

Rewards were banana pellets for all but one chimpanzee and grapes for the bonobos and the remaining chimpanzee (who was unmotivated by pellets).

Process

Preparation

Subjects completed several training phases to ensure thorough comprehension of the test state of affairs. First, they learned how to access the ropes fastened to the platforms (door training) later on which they were introduced to the total appliance and the reward dispersal of the corresponding experimental condition (apparatus familiarization). In both weather condition, subjects and then had to demonstrate apparatus understanding by completing two criterion tests, once past successfully responding to a partner'south choices (responder preparation) and once by operating the apparatus lone on both sides (open-door training). Only subjects who reached criterion proceeded to the test. Finally, subjects in both atmospheric condition received experience on both sides of the apparatus with a barrier occluding the responder's view of all towers (barrier feel). This was washed to familiarize subjects with the barrier and for them to experience how the bulwark obstructed ane'due south view in the responder position (in this phase the apparatus was rigged and so that in both weather subjects were rewarded equally often in the presence of a barrier prior to examination). For details on all training steps and criterion tests see 'detailed grooming procedures' in Supplementary Information.

Exam

Subjects acted as the proposer and a conspecific partner as responder. A barrier occluded the responder's view of two towers. Subjects could see all four towers (see Fig. 1 for view from subject'south perspective). In addition to completing the preparation phases partners received boosted feel with the barrier to ensure they responded in ways that maximized their nutrient intake – i.east. to match the field of study's pick if the subject field had chosen a visible pick and to cull randomly between the hidden options if the discipline had chosen behind the barrier (this was the aforementioned in both conditions – the partner'due south aim was always to match the subject's option whereas whether or not the subject area was incentivized to facilitate a match depended on the condition). Partners performed their task very reliably and fabricated merely few mistakes then that, overall, they successfully matched the bailiwick'due south pick in 98.0% of trials when subjects had chosen a visible choice and in 44.6% of trials (i.east. close to the 50% chance level) when subjects had chosen an selection behind the barrier.

The exam consisted of two sessions of 12 trials (for a total of 24 trials), with the barrier position being swapped halfway through each session. Which towers were covered first was counterbalanced across subjects.

Study 1b

Grooming and test was identical to Study 1a except that subjects who had previously taken function in the cooperation condition participated in the competition status (and vice versa) in a within-subjects pattern.

Follow-upwards preference test

Subjects

Sixteen chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes, ix females, M historic period = 25 years) and iv bonobos (Pan paniscus, 3 females, M age = fifteen years) participated. Three further chimpanzees and one bonobo took part as stooge partners. Viii chimpanzees and three bonobos had also taken role in Written report 1.

Apparatus

The apparatus consisted of four plastic trays (8 × eight cm), each with a string fastened. Trays each contained two rewards and were placed in the aforementioned position every bit the towers in the main experiment. Subjects could access the nutrient in the proposer position by pulling on the strings. Partners in the responder position could not access any food and remained passive.

Procedure

Training

Earlier the test subjects demonstrated that they understood how to admission the trays and received feel with a full barrier as in Study ane (see Supplementary Information).

Test

Subjects were in the proposer and the partner in the responder position. A barrier occluded the partner's view of ii trays while all trays were visible to the subject. The barrier position was switched halfway through the session and was counterbalanced in the same fashion as in Study ane. Subjects completed two sessions of 12 trials.

Study 2

Participants

40-8 four-year-olds (M age = 4.55 years, 50% girls) participated in the study. Children mostly came from eye class backgrounds and were recruited and tested at urban daycare centers. 1 boosted kid failed to pass the training criteria and was excluded from the examination. Children were randomly assigned to the cooperation and competition conditions in a between-subjects design.

The written report was conducted in compliance with the ethical principles of the American Psychological Association (APA) and was approved past the internal Ideals Commission of the Max Planck Constitute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Children'due south participation occurred with their parent'southward informed consent, was voluntary, and could be refused or terminated at any time.

Apparatus and design

The general task was the same equally for the apes except for the following changes. Instead of operating decision doors and pulling on ropes, children pulled out the platforms straight and were told they could only make 1 choice per round. In the cooperation condition, a sliding door was in the bottom of the appliance on both sides. At the cease of each circular, the experimenter opened the sliding doors and – if players had coordinated successfully – each player could recollect one advantage (otherwise both received nothing).

In the competition condition, the sliding door on the proposer side was moved up to the level of the lower platforms (for the responder it remained at the bottom). The responder could thus admission all rewards at the bottom of the apparatus whereas the proposer had sectional access to all rewards remaining on the lower platforms resulting in the same payoff structure as in Study 1 (Fig. 1).

Cerise and golden marbles were used as rewards at training and examination, respectively.

Procedure

Preparation

The training closely resembled that of Written report 1. Children were starting time familiarized with the apparatus (apparatus familiarization) and introduced to the partner (a same-sex activity puppet played past a 2d experimenter). Children so completed two benchmark tests (responder training and open up-door training) to demonstrate apparatus agreement and gained experience with a bulwark roofing the all towers from the responder's perspective (bulwark experience). As in Study 1, rewards were dispersed during grooming co-ordinate to the experimental status to familiarize participants to the corresponding social context (i.east. cooperation versus competition). To accommodate the constraint that testing had to be completed within one day, sessions were shortened and some minor grooming features replaced by exact instructions (come across Supplementary Information).

Test

The full general exam was the aforementioned as for the apes. To keep motivation high, golden marbles were introduced every bit rewards. The test consisted of half-dozen trials and afterward three trials the position of the bulwark was swapped (the starting position was balanced). As in Study i, the partner chose in a way that maximized her payoff. That is, in both conditions the partner matched children's choices if they chose a visible option and chose randomly between the two hidden options if children chose backside the barrier.

After completing the test children were asked the ii mail-test questions after which they fabricated a necklace with the marbles nerveless during the game.

Follow-upwards preference test

Participants

Twenty-four iv-year-olds (Grand age = 4.56 years, 50% girls) participated.

Apparatus

The apparatus was the same as in Written report 2 except that the lower platforms were removed so that participants could release the rewards alone. Children played with the same puppet every bit in Study 2.

Procedure

Training

Before test, children successfully retrieved the rewards in a training process closely matching that of Study 2. As in Study 2, children also received experience with a full barrier (see Supplementary Information).

Examination

A barrier occluded the partner's view of ii towers while all towers were visible to the subject. Children completed six trials. The barrier position was switched halfway through the session.

Coding

For each trial of Studies one and 2, we coded whether subjects chose a tower behind the barrier (subconscious) or a tower the responder could see (visible) and whether or not this choice was the right 1 (i.eastward. visible in the cooperation condition and hidden in the contest status).

Children'southward responses to the firs post-test question were coded equally referring to visible or hidden towers, and as correct (referring to visible towers in the cooperation condition and to hidden towers in the competition status) or incorrect. Responses to the second question were coded every bit referring to the responder'southward perceptual or knowledge state or not.

Choices in the follow-upwardly preference tests were coded as visible or subconscious.

Analysis

All models were fitted in R51 using the functions 'glm' (for Generalized linear models) and 'glmer' (for Generalized Linear Mixed Models) of the R-package lme452. For all models, we ran several model diagnostics. These were all uncomplicated. If at that place were multiple test predictors we always showtime compared a full model with a null model non including the examination predictors but retaining all control predictors, random intercepts, and random slopes. We only tested for potential effects of individual test predictors if the full-null model comparing indicated that all test predictors combined significantly afflicted the response. For detailed model descriptions and outputs see Supplementary Tables 2–five.

References

-

Hare, B., Call, J. & Tomasello, M. Do chimpanzees know what conspecifics know and do not know? Anim.50 Behav. 61, 139–151 (2001).

-

Melis, A. P., Call, J. & Tomasello, M. Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) conceal visual and auditory data from others. J. Comp. Psychol. 120, 154–162 (2006).

-

Hare, B., Call, J. & Tomasello, Thou. Chimpanzees deceive a human competitor by hiding. Cognition 101, 495–514 (2006).

-

Bräuer, J., Telephone call, J. & Tomasello, Grand. Chimpanzees really know what others can see in a competitive situation. Anim. Cogn. 10, 439–448 (2007).

-

Karg, K., Schmelz, G., Call, J. & Tomasello, M. The goggles experiment: Tin can chimpanzees utilise cocky-experience to infer what a competitor can see? Anim. Behav. 105, 211–221 (2015).

-

Kaminski, J., Call, J. & Tomasello, Thousand. Chimpanzees know what others know, but not what they believe. Cognition 109, 224–234 (2008).

-

Schmelz, M., Call, J. & Tomasello, K. Chimpanzees know that others brand inferences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 3077–3079 (2011).

-

Kano, F. & Telephone call, J. Neat apes generate goal-based action predictions: An eye-tracking study. Psychol. Sci. 25, 1691–1698 (2014).

-

Herrmann, Eastward., Hare, B., Call, J. & Tomasello, M. Differences in the cognitive skills of bonobos and chimpanzees. PLoS Ane 5, e12438 (2010).

-

Kaminski, J., Phone call, J. & Tomasello, Grand. Body orientation and face up orientation: two factors controlling apes' begging beliefs from humans. Anim. Cogn. 7, 216–223 (2004).

-

MacLean, E. L. & Hare, B. Bonobos and chimpanzees infer the target of another'due south attention. Anim. Behav. 83, 345–353 (2012).

-

Krupenye, C., MacLean, E. & Hare, B. Does the bonobo have a (chimpanzee-similar) theory of mind? In Bonobos: Unique in heed, brain and behavior (Oxford: Oxford University Printing, in printing).

-

Tomasello, M. Why We Cooperate (Cambridge, MA: MIT Printing, 2009).

-

Henrich, J. The Undercover of Our Success: How Culture is Driving Man Evolution, Domesticating Our Species, and Making Us Smarter (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Printing, 2016).

-

Povinelli, D. J. & Eddy, T. J. Chimpanzees: Join visual attending. Psychol. Sci. 7, 129–135 (1996).

-

Povinelli, D. J., Bierschwale, D. T. & Cech, C. 1000. Comprehension of seeing as a referential act in immature children, but non juvenile chimpanzees. Brit. J. Dev. Psychol. 17, 37–60 (1999).

-

Call, J., Agnetta, B. & Tomasello, M. Social cues that chimpanzees do and do not apply to find hidden objects. Anim. Cogn. three, 23–34 (2000).

-

Itakura, Southward., Agnetta, B., Hare, B. & Tomasello, M. Chimpanzee use of human being and conspecific social cues to locate hidden food. Dev. Sci. 2, 448–456 (1999).

-

Hare, B. Tin can competitive paradigms increase the validity of social cognitive experiments on primates? Anim. Cogn. four, 269–280 (2001).

-

Hare, B. & Tomasello, M. Chimpanzees are more skilful in competitive than in cooperative cognitive tasks. Anim. Behav. 68, 571–581 (2004).

-

Lyons, D. E. & Santos, 50. R. Ecology, domain specificity, and the origins of theory of mind: is competition the catalyst? Philos. Compass. 1, 481–492 (2006).

-

Wimmer, H. & Perner, J. Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of incorrect beliefs in young children's understanding of charade. Cognition xiii, 103–128 (1983).

-

Tomasello, M. & Haberl, K. Agreement Attention: 12- and 18-Month-Olds Know What Is New for Other Persons. Dev. Psychol. 39, 906–912 (2003).

-

Buttelmann, D., Carpenter, M. & Tomasello, M. Eighteen-month-old infants testify false belief understanding in an agile helping paradigm. Cognition 112, 337–342 (2009).

-

Schmelz, M. & Call, J. The psychology of primate cooperation and competition: A telephone call for realigning research agendas. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 371, 20150067 (2016).

-

Herrmann, E. & Tomasello, K. Apes' and children's agreement of cooperative and competitive motives in a chatty state of affairs. Dev. Sci. nine, 518–529 (2006).

-

Behne, T., Carpenter, M. & Tomasello, Chiliad. One-year-olds embrace the communicative intentions behind gestures in a hiding game. Dev. Sci. 8, 492–499 (2005).

-

Moore, R., Müller, B., Kaminski, J. & Tomasello, G. 2-yr-old children but non domestic dogs understand chatty intentions without language, gestures, or gaze. Dev. Sci. 18, 232–242 (2015).

-

Schulze, C. & Tomasello, M. 18-calendar month-olds comprehend indirect communicative acts. Cognition 136, 91–98 (2015).

-

Tomasello, One thousand., Melis, A., Tennie, C., Wyman, East. & Herrmann, E. Two key steps in the evolution of human cooperation: The interdependence hypothesis. Curr. Anthropol. 53, 673–692 (2012).

-

Sterelny, G. The Evolved Apprentice (Cambridge: MIT Printing, 2012).

-

Boesch, C. & Boesch, H. Hunting behavior of wild chimpanzees in the Taï National Park. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 78, 547–573 (1989).

-

Nishida, T. & Hosaka, G. Coalition strategies amidst adult male person chimpanzees of the Mahale Mountains, Tanzania. In Great Ape Societies (eds. McGrew, W. C, Marchant, Fifty.F, & Nishiday T.) 114–134 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

-

Muller, One thousand. N. & Mitani, J. C. Disharmonize and cooperation in wild chimpanzees. In Advances in the Study of Behavior (eds. Slater, P. J. B., Rosenblatt, J., Snowdon, C., Roper, T. & Naguib, Thousand.) 275–331 (New York: Elsevier, 2005).

-

Surbeck, K. & Hohmann, G. Primate hunting past bonobos at Luikotale, Salonga National Park. Curr. Biol. 18, R906–R907 (2008).

-

Tokuyama, N. & Furuichi, T. Do friends help each other? Patterns of female person coalition formation in wild bonobos at Wamba. Anim. Behav. 119, 27–35 (2016).

-

Hirata, S. & Fuwa, Grand. Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) acquire to human activity with other individuals in a cooperative job. Primates 48, 13–21 (2007).

-

Hare, B., Melis, A. P., Woods, V., Hastings, S. & Wrangham, R. Due west. Tolerance allows bonobos to outperform chimpanzees on a cooperative task. Curr. Biol. 17, 619–623 (2007).

-

Melis, A. P. & Tomasello, Chiliad. Chimpanzees' (Pan troglodytes) strategic helping in a collaborative task. Biol. Lett. 9, 20130009 (2013).

-

Duguid, S., Wyman, Eastward., Bullinger, A. F., Herfurth-Majstorovic, M. & Tomasello, 1000. Coordination strategies of chimpanzees and human children in a Stag Chase game. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. (Biol) 281, 20141973 (2014).

-

Grueneisen, South., Wyman, E. & Tomasello, Thousand. Children use salience to solve coordination issues. Dev. Sci. 18, 495–501 (2015).

-

Moll, H. & Tomasello, Yard. Level 1 perspective-taking at 24 months of age. Brit. J. Dev. Psychol. 24, 603–613 (2006).

-

Moll, H. & Meltzoff, A. Due north. How Does It Look? Level ii Perspective-Taking at 36 Months of Age. Child Dev. 82, 661–673 (2011).

-

Völter, C. J., Rossano, F. & Telephone call, J. From exploitation to cooperation: Social tool use in orang-utan mother–offspring dyads. Anim.l Behav. 100, 126–134 (2015).

-

Karg, K., Schmelz, K., Call, J. & Tomasello, Thou. Chimpanzees strategically dispense what others can see. Anim. Cogn. 18, 1069–1076 (2015).

-

Crockford, C., Wittig, R. G., Mundry, R. & Zuberbühler, One thousand. Wild chimpanzees inform ignorant group members of danger. Curr. Biol. 22, 142–146 (2012).

-

Flavell, J. H., Everett, B. A., Croft, K. & Flavell, E. R. Young children's knowledge almost visual perception: Further evidence for the level 1-level two distinction. Dev. Psychol. 17, 99–103 (1981).

-

Grueneisen, S., Wyman, E. & Tomasello, M. I know you don't know I know.: Children utilize second-club simulated belief reasoning for peer coordination. Child Dev. 86, 287–293 (2015).

-

Kohn, A. No Contest: The Instance Against Competition (New York: Houghton Miffin Visitor, 1992).

-

Moll, H., Carpenter, M. & Tomasello, M. Social engagement leads ii-year-olds to overestimate others' knowledge. Infancy sixteen, 248–265 (2011).

-

R Cadre Squad. R: A language and environment for statistical calculating. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Republic of austria. http://www.R-project.org/ (2014).

-

Bates, D., Maechler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, Due south. lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using Eigen and S4. R package version one.ane–7, http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=lme4 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank Raik Pieszek for constructing the apparatuses, Miriam Richter for her help testing the apes, and the animal caretakers of the zoo Leipzig. We give thanks Isabelle de Gaillande-Mustoe for helping with the kid study, Roger Mundry for statistical advice, and all children, parents, and daycare centers for their friendly cooperation.

Author data

Affiliations

Contributions

S.G., S.D., H.Southward., and M.T. designed the report. H.S. and S.D. collected the data and South.G. and D.Yard. performed the statistical analyses. S.G., S.D., and M.T wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding writer

Ideals declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Boosted information

Publisher'south note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary fabric

Rights and permissions

Open Access This commodity is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution iv.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in whatever medium or format, every bit long as you requite appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and point if changes were made. The images or other third party cloth in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the textile. If textile is not included in the article'south Creative Eatables license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, y'all will demand to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/4.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grueneisen, S., Duguid, S., Saur, H. et al. Children, chimpanzees, and bonobos adjust the visibility of their actions for cooperators and competitors. Sci Rep 7, 8504 (2017). https://doi.org/ten.1038/s41598-017-08435-7

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1038/s41598-017-08435-vii

Further reading

Comments

By submitting a comment you concur to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If yous find something calumniating or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag information technology as inappropriate.

mahomedswithimince.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-017-08435-7

0 Response to "Bonobos Capture Baby Monkeys and Use Them as Doll"

Post a Comment